While planning for trekking in Nepal, individuals imagine snow-covered mountain peaks, prayer flags, snowcapped mountains, and zigzag trails. The potential of being face-to-face with Mount Everest or going trekking through the high passes of Annapurna excites thousands of visitors every year. Yet, with the thrill of adventure comes a challenge that even the fittest of athletes cannot afford to ignore, which is the chance of occurrence of altitude sickness.

Altitude sickness, also known as acute mountain sickness (AMS), is the body's reaction to reduced oxygen levels at higher elevations. Unlike other health conditions, it does not discriminate. Whether you're a seasoned trekker, a marathon runner, or someone trekking for the first time, altitude sickness can affect anyone.

Symptoms of altitude sickness can include headache, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, fatigue, shortness of breath, and difficulty sleeping. In severe cases, altitude sickness can lead to High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) or High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE), which can be life-threatening if not treated promptly.

To prevent altitude sickness, it's important to acclimate gradually by spending a few days at intermediate elevations before going to higher elevations. It's also recommended to stay well hydrated, avoid alcohol and sleeping pills, and avoid overexertion. Treatment for altitude sickness may include oxygen therapy, descent to a lower altitude, or medication such as acetazolamide.

Suppose you plan to travel to high altitudes. In that case, it's essential to consult with a healthcare professional and be aware of the symptoms of altitude sickness. Altitude Sickness occurs at high altitude. The decrease in atmospheric pressure makes it difficult to breathe due to the reduced oxygen levels. Mainly, it happens above 3300m(10,000ft). This is the most dangerous hazard that threatens trekkers. Every year, more trekkers are victims of altitude sickness because they do not take care of themselves properly when in the mountains.

This blog is a complete guide to understanding altitude sickness for trekkers planning their Himalayan adventure. Here, we'll explain:

What is altitude sickness, and why does it matter?

- The symptoms to watch out for at different stages

- Practical prevention strategies such as acclimatization and pacing

- Effective medications and treatments are available

- Objective trekking advice for safe and enjoyable high-altitude travel

Suppose you are trekking to popular classical trekking routes like the Everest Base Camp, Annapurna Base Camp, Annapurna Circuit, Manaslu Circuit, or Langtang Valley. In that case, this information will guide you to safe trekking and to relish the beauty of Nepal.

What is Altitude Sickness or Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)?

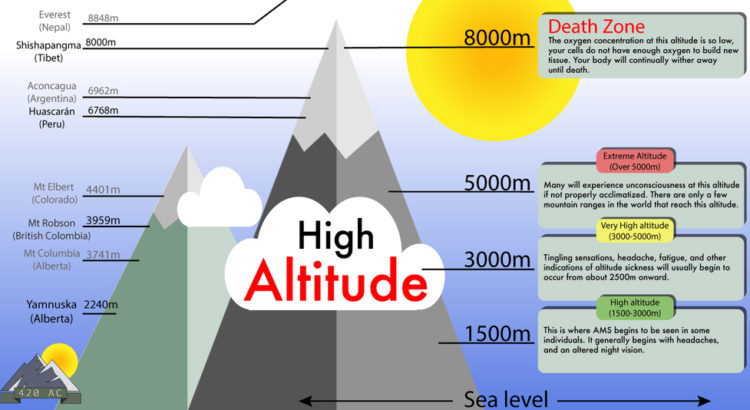

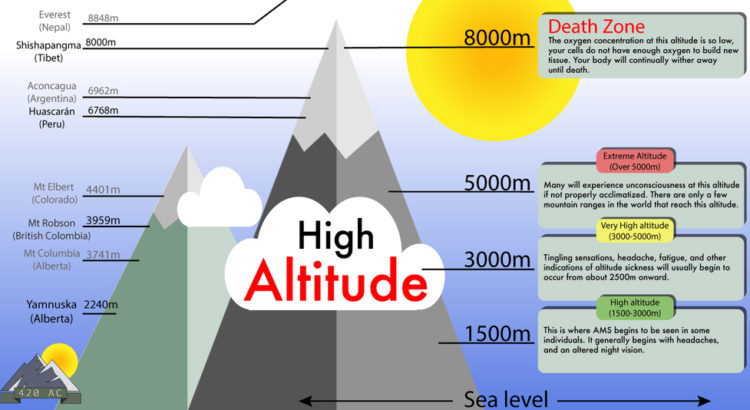

Altitude sickness is a condition that occurs when the body fails to adjust to the lower oxygen levels at a higher altitude. At sea level, oxygen is about 21%, and your body functions with ease. But as you go higher than 2,500 meters (8,200 feet), pressure decreases, and with each breath, less oxygen in the air enters your lungs and blood.

Here is a comparison for better understanding:

- Sea level (0 m): Blood oxygen saturation is around 98–100%.

- 3,000 m (9,842 ft): Oxygen levels drop, and saturation can dip to around 90%.

- 5,500 m (18,000 ft): The body can only get 50%–60% of the oxygen it would at sea level.

- 8,848 m (Everest summit): Oxygen is so low that climbers require supplemental oxygen to breathe.

When your body is unable to acclimatize quickly enough, the lower oxygen level triggers a series of symptoms such as headache, nausea, dizziness, and fatigue. This is altitude sickness.

Here's something to keep in mind: altitude sickness has nothing to do with fitness. A fit athlete can develop it, but a slightly older trekker might acclimatize better. Genetics, ascent rate, and acclimatization are far more critical than how strong or fit you are.

Why Does it Matter to Trekkers and Travelers?

Altitude sickness is among the most frequent causes of evacuation on treks in Nepal. For example, during the Everest Base Camp Trek, nearly 30–40% of trekkers develop mild to moderate symptoms of AMS at some point. On longer and higher treks like the Manaslu Circuit or the Annapurna Circuit, the risk can be even higher because of several high passes.

Why does knowing altitude sickness matter?

- It Can Happen to Anyone: No matter what your age, sex, or fitness level, altitude sickness can occur to anyone at any time. An athletic, young trekker might do poorly at 3,500m, whereas a slower, older trekker gets on fine.

- Mild Symptoms Can Quickly Get Worse: Ignoring a mild headache or dizziness at 3,000m can lead to life-threatening HAPE or HACE higher up.

- Isolation Area Challenges: The majority of Nepal's trekking paths are inaccessible. Medical facilities are few, helicopter evacuation is costly, and weather delays could render a quick rescue improbable. Prevention of altitude sickness is far better than curing it after it sets in.

- Your Trek Experience is at Stake: Even mild symptoms, such as insomnia, loss of appetite, and drowsiness, can make trekking challenging. Instead of taking in the views, you will suffer if you fail to acclimatize appropriately.

For trekkers and travelers in Nepal, knowledge of altitude sickness is not convenient; it is life or death, and making the most of your Himalayan journey.

Recommendation Read: How often do people get Altitude Sickness at Everest Trek

What Are the Three Stages of Altitude Sickness?

Altitude sickness does not manifest the same way in every trekker. Its symptoms can range from mere discomfort to life-threatening complications. Understanding the stages allows you to know when to rest, when to descend, and when to seek urgent medical care.

Mild Altitude Sickness (Mild AMS)

This is the most common stage that happens to trekkers. Symptoms usually begin 12–24 hours after reaching high altitude.

Symptoms commonly seen are:

- Headache (most common indicator)

- Fatigue and weakness

- Dizziness or drowsiness

- Nausea, sometimes with vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Difficulty in sleeping (restless nights, frequent waking)

Example: Trekkers on the Everest Base Camp trip tend to experience these symptoms upon arrival in

Namche Bazaar (3,440m) or

Dingboche (4,410m). These are typical signs that the body is adapting to altitude.

What to do: Rest, hydrate, avoid drinking alcohol, and allow your body time to acclimatize. Most recover within 1–2 days if they don't go higher.

Moderate Altitude Sickness

If the mild AMS is overlooked, the symptoms progress to the moderate level. In this regard, trekking becomes painful and risky.

Symptoms are:

- Tough headache that does not respond to medication

- Repeated vomiting and nausea

- Shortness of breath, even when resting

- Weakness, loss of coordination (unsteadiness walking in a straight line)

- Persistent fatigue

At Lobuche (4,940m) or Gokyo (4,800m), trekkers may develop moderate AMS if they ascend too quickly from Tengboche or Namche without adequate rest days.

What to do: Halt climbing immediately. Rest at the initial altitude or descend if symptoms worsen. Supplemental oxygen and medication (such as dexamethasone or acetazolamide) may be needed.

Deadly Severe Altitude Sickness (HAPE/HACE)

Severe altitude sickness can progress rapidly and is fatal if it's not treated.

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE): Liquid builds up in the lungs, which can have severe problems for the body, and if not cured in a proper time, can have life-threatening consequences.

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE): Liquid builds up in the brain, which can have severe problems for the body, and if not cured in a proper time, can have life-threatening consequences.

Symptoms are:

- Too much breathlessness even when resting

- Cough with pink or frothy sputum (HAPE indicator)

- Staggering and inability to walk in a straight line (ataxia)

- Hallucinations, confusion, or irrational behavior (HACE indicator)

- Blue-gray fingernails/lips (hypoxia)

- Not being able to remain conscious in severe AMS

Example: Trekkers climbing Thorong La Pass (5,416m) on the Annapurna Circuit trek may develop extreme AMS if they ascend too rapidly from Manang without proper acclimatization.

What to do: The only safe thing to do is immediate descent. Horse, porter, or helicopter transport may be necessary. Supplemental oxygen or portable hyperbaric chambers (Gamow bags) can keep trekkers stable until descent is possible.

Symptoms of Altitude Sickness

Identifying the signs of altitude sickness at an early stage is crucial for avoiding its severe form. Trekkers often confuse the symptoms with exhaustion, dehydration, or even foodborne illness. Although these conditions may occur as well, it's safer to suspect altitude in the Himalayas when trekking.

Common Symptoms Experienced During Altitude Sickness

Most trekkers will show symptoms once they have ascended to 2,500–3,000 meters. These usually begin within 12–24 hours after an increase in altitude.

- Headache: The classic symptom. If you get a headache at altitude, especially accompanied by other symptoms, then consider AMS.

- Fatigue and weakness: After a good night's sleep, you might feel exceedingly weak.

- Dizziness or feeling faint: Even mundane activities like getting up or turning sharply might result in loss of balance.

- Taste: The taste is unpleasant, and you'll likely try to force the food down.

- Nausea or vomiting: May be mild or prolonged, occasionally worsening with further ascent.

- Insomnia: Most trekkers complain about being woken repeatedly, often with shallow respirations (periodic breathing).

- Breathlessness: At higher altitudes, you may feel short of breath even when resting.

On the Everest Base Camp trek, most trekkers initially experience these symptoms only after arrival in Namche Bazaar (3,440m). For this reason, most itineraries feature a rest day there to facilitate acclimatization.

How to Distinguish Mild Symptoms from Serious Ones

It's normal to feel a little uncomfortable when acclimatizing. But the distinction between mild and hazardous symptoms is often fine. Here's how to differentiate:

- Mild (Normal Acclimatization): Headache, mild nausea, fatigue, restless sleep. It resolves with rest, hydration, and an extra acclimatization day.

- Moderate (Warning Zone): Frequent headache, vomiting, dizziness, dyspnea at rest, impaired coordination. These tell you to stop climbing and consider descent.

- Severe (Medical Emergency): Confusion, inability to walk, severe dyspnea, coughing up frothy sputum, or loss of consciousness. These are symptoms of HAPE or HACE and require immediate descent and evacuation.

Tip: If you are unable to walk in a straight line (ataxia) or enunciate clearly, it's a medical emergency.

Can You Get Altitude Sickness at 2,000 Feet?

A few hikers wonder if altitude sickness can happen at pretty low altitudes. At 2,000 feet (610 meters) above sea level, oxygen concentrations are equivalent to those at sea level. This elevation is far below the point at which AMS happens.

But other things can cause dizziness or fatigue, like dehydration, heat, or poor physical health. These are not altitude sickness symptoms.

Who is More Vulnerable at Lower Altitudes?

While AMS doesn't occur at 2,000 feet, certain groups will still experience low-altitude hikes as uncomfortable:

- Those with lung or heart disease (e.g., COPD, asthma, coronary heart disease).

- Those with anemia, who already have a compromised oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Individuals not used to any physical exercise—fatigue may be indistinguishable from altitude fatigue.

Context in Nepal: Kathmandu is at 1,400m (4,593 ft). Nobody develops altitude sickness there, yet trekkers frequently feel tired due to jet lag, pollution, or dehydration upon arrival.

Can You Get Altitude Sickness at 5,000 Feet?

At 5,000 feet (1,524m), there is enough oxygen to let the vast majority of individuals function normally. However, individuals with altitude sickness can develop mild symptoms like headache or drowsiness, especially if they ascend too rapidly.

The risk becomes evident after 8,000–10,000 feet (2,500–3,000m). For that reason, AMS is so common on Himalayan treks from Lukla (2,860m) or Manang (3,540m).

Factors That Affect Susceptibility

Not everyone reacts the same way to altitude. Several factors determine who gets symptoms and who does not:

- Ascent Temperature: Climbing too fast is the most significant individual cause. Trekkers who fly directly into Lukla (2,860m) tend to experience minor symptoms on day one.

- Genetics: Certain people are naturally more resistant or vulnerable. Even Sherpas who grow up at high altitude can be affected if they climb too fast.

- Age and Fitness: Surprisingly, young and fit trekkers may push themselves harder and ignore symptoms, increasing risk. Older trekkers often go slower and acclimatize better.

- Hydration and Nutrition: Dehydration exacerbates symptoms, whereas a carbohydrate-rich diet aids the body's adaptation.

- Previous Exposure: If you've been at altitude before, your body may adapt faster the next time.

Example: On the Annapurna Circuit, even at Chame (2,650m) or Pisang (3,200m), some trekkers may develop symptoms if they have climbed too quickly. At Manang (3,540m), acclimatization days are necessary.

Acute Mountain Sickness: What Does It Mean?

Definition and How It Relates to Altitude Sickness?

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) is the official medical term for altitude sickness. It describes the collection of symptoms caused by the body's inability to adjust to reduced oxygen levels at increasing heights.

AMS is the most common form of altitude illness and typically the first warning sign that you are ascending too quickly. Almost every trekker who reaches over 3,500m will experience some form of AMS, even when mild.

AMS = Acute Mountain Sickness in its onset.

When does AMS Requires Emergency Treatment?

Mild AMS is usual and usually manageable. But AMS is dangerous when:

- Symptoms worsen instead of decreasing with rest.

- You experience an extreme headache, vomiting, and breathlessness.

- You become confused, staggering, or irrational.

- Breathing becomes difficult even when staying still.

Here, AMS is developing into HAPE or HACE, which are lethal. The choice is to drop immediately and get medical care.

Nepal Trek Example: During the Everest Base Camp trek, mountaineers ascending too quickly from Namche (3,440m) to Tengboche (3,860m) without proper resting sometimes get AMS. If they ignore signs and continue to Dingboche (4,410m), risks become exponentially worse.

How to Prevent Altitude Sickness?

Prevention of altitude sickness is simply about giving your body enough time to acclimatize to thinner air gradually. With proper planning, most trekkers can finish their trek without serious issues. There are some specific strategies that trekkers can adapt to prevent altitude sickness. Some of them are briefly explained below:

Acclimatization Strategies/ Altitude Sickness Prevention

Climb Gradually: The golden rule is "Do not ascend more than 300–500m per day once above 3,000m." If your itinerary does have larger gains, rest days must always be included. Example: During the Everest Base Camp Trek, trekkers rest at Namche Bazaar (3,440m) and Dingboche (4,410m) to allow the body to acclimatize.

Climb High, Sleep Low: During acclimatization days, trekkers ascend to higher altitudes but sleep at lower ones. Example: From Dingboche, many climb to Nagarjun Hill (5,100m) for the day, then sleep at 4,410m.

Rest Days Are Not Lazy Days: Acclimatization days must have light exercise, such as short walks. Sitting idle all day can slow the acclimatization process.

Recognize the "Danger Zone": Most AMS are between 3,000 and 5,000m. Above 5,000m, dangers are greater, but by then most trekkers have acclimatized step by step.

Hydration, Pacing, and Lifestyle Tips

Drink Plenty of Water: Dehydration worsens AMS symptoms. Drink 3–4 liters per day. Urine must be pale-colored, not dark.

Avoid Alcohol and Smoking: Alcohol can slow down breathing, which makes it harder for your body to get oxygen. Smoking also lowers lung function.

Pace Yourself: Walk, mainly uphill. One of the most frequent mistakes is trying to "keep up with speedier trekkers." Walking too quickly is a recipe for AMS.

Eat High-Carbohydrate Foods: Rice, pasta, potatoes, and bread provide fast energy. Carbohydrates require less oxygen to burn than fats and proteins, making them a better fuel at high altitude.

Sleep Smart: If you can't sleep, try raising your head a bit higher or practicing deep breathing. Avoid taking sleeping pills (they slow down night breathing).

Listen to Your Body: Never ignore recurring headaches, nausea, or dizziness. Halt climbing when symptoms worsen.

Pro-Tip from Trekking Planner Nepal: Add extra days to your trekking itinerary. A trek with 1–2 buffer days not only acclimatizes you better but also provides you with a greater possibility of completing the trek.

Altitude Sickness Medication

Prevention is impossible at times, particularly on high-altitude treks where rates of climb can't always be controlled. In these cases, medicines reduce the severity of symptoms.

Medicines Used Most Often

Acetazolamide (Diamox): Most commonly prescribed altitude sickness medication. Helps your body acclimatize faster by acidifying blood, which stimulates breathing. Preventatively (before they develop symptoms) as well as treatment (if they do).

Dexamethasone: A steroid that reduces swelling in the brain caused by altitude sickness. Typically used in emergencies when coming down is not an immediate possibility.

Nifedipine: It is used for HAPE (High Altitude Pulmonary Edema). Lowers blood pressure in the lungs, alleviating fluid buildup.

Ibuprofen / Paracetamol: It can be used for headache relief.

Note: If you are taking painkillers daily for a headache, it's a red flag. The problem may not be just pain—it could be AMS. Similarly, Trekking Planner Nepal does recommend using medicine to control altitude sickness. So, it must be done with a prescription from medical personnel. We don't sell, promote, or recommend the use of any pharmaceuticals for the treatment of altitude sickness.

Guidelines for Safe Use

- Always consult a doctor before taking any altitude medication.

- Do not use Diamox as a replacement for acclimatization. It assists, but gradual ascent is still the best prevention.

- Preventive Diamox doses: Some trekkers take 125–250mg twice daily from the day before ascent.

- Do not self-medicate with steroids except in an emergency. These medications can suppress symptoms, providing a false sense of security.

High Altitude Sickness Treatment

Despite best practice, some trekkers will get altitude sickness. Treatment depends on severity. While there can be some first aid taken before the onset of altitude sickness, once affected, the individual does require immediate medical attention. So here are some of the things to consider for the treatment of high altitude sickness.

Immediate Care Steps

- Stop climbing at once.

- Rest and hydrate.

- For a headache, take a painkiller (ibuprofen or paracetamol).

- If symptoms don't show improvement within 24 hours, descend.

Oxygen Therapy and Descent

- Supplemental oxygen can quickly ease symptoms.

- Descent is the final solution. A descent by just 500–1,000m often results in quick recovery.

- Some treks offer portable hyperbaric chambers (Gamow bags)—inflatable pressure bags that mimic lower altitudes until descent becomes feasible.

When to Get Medical Assistance

Get medical evacuation if:

- Symptoms become worse despite rest.

- You experience confusion, staggering, or severe shortness of breath.

- You are unable to walk or think clearly.

Trekking Example: Trekkers on the Annapurna Circuit, when they get severe AMS at Thorong Phedi (4,450m), typically descend quickly to Manang (3,540m), where recovery is easier at a lower elevation and with improved medical attention.

Most trekkers assume that once they reach lower altitudes or are home, symptoms of altitude sickness vanish immediately. While this occurs in most people, in some individuals, the symptoms persist or arise even after descent.

Why Symptoms May Occur or Last After Descent

Retarded Fluid Accumulation: Symptoms may persist for hours or even days following descent to lower altitudes in HAPE (fluid accumulation in the lungs) or HACE (fluid accumulation in the brain).

Respiratory Infections: Immunocompromise resulting from exposure to cold, high-altitude conditions during trekking can lead to coughs, bronchitis, or pneumonia that could masquerade as chronic altitude sickness.

Fatigue and Dehydration: Physical effort at high altitude, dehydration, or fatigue can result in similar symptoms to mild AMS.

Pre-existing Health Issues: At times, exposure to altitude will unveil previously unsuspected heart or lung conditions, which continue to cause problems later on.

Management of Delayed Symptoms

Rest and Hydrate: Give your body time to relax after reaching home. Fluids must be had, and balanced meals must be consumed.

Medical Check-Up: If you are experiencing cough, breathlessness, or headaches for longer than a few days, consult a doctor.

Avoid Immediate Re-Ascent: If you are planning another trek, have at least a week or two of rest before returning to altitude.

Monitor Mental Health: Sometimes, post-trek tiredness and mild mental symptoms may persist. Adequate rest generally takes care of these.

Example: A few trekkers descending from Everest Base Camp report fatigue, cough, or headaches for a day or two in Kathmandu. Symptoms typically improve with rest and hydration.

How Long Does Altitude Sickness Last?

Altitude sickness lasts anywhere from a few hours to several days or even longer, depending on the severity, your body's response, and how quickly you descend.

- Mild AMS: Typically improves in 24–48 hours with rest and fluid at the same elevation or after coming down.

- Mild AMS: Can take 2–4 days to recover fully, even after descent.

- Severe AMS (HAPE or HACE): Must be treated immediately. Full recovery takes weeks and sometimes necessitates hospitalization.

Determinants of Duration

- Speed of Ascent: The faster you climb, the more time it will take to recover.

- Age and Fitness: Fitter and younger walkers may recover faster, while older walkers take longer.

- Availability of Medical Attention: Climbers with supplemental oxygen or proper treatment generally recover more quickly.

- Individual Sensitivity: Some people acclimate better than others, depending on their genetics.

- Important Reminder: Never "push through" symptoms hoping they will pass. Slight AMS may improve with time, but deteriorating symptoms require immediate descent.

Conclusion

Nepal's breathtaking Himalayas are a dream trek. Still, altitude sickness is a very real barrier that all trekkers should be prepared for. The condition is not age, fitness, or experience related. So it can strike anyone.

The following are the key points:

- Altitude sickness: not enough oxygen at higher elevations.

- Symptoms to watch out for: headache, dizziness, lethargy, nausea, and poor sleep.

- Prevention: gradual ascent, plenty of water intake, and rest days are essential.

- Treatment: cease going higher if there are symptoms; come down if they worsen.

- Medications: Diamox, dexamethasone, and nifedipine may be helpful, but never replace acclimatization.

- Emergency: High-altitude AMS (HAPE/HACE) requires immediate descent and medical attention.

By doing good planning, being aware, and having a reputable trekking agency like Trekking Planner Nepal, you can minimize risks and enjoy your high-altitude trek in safety. Remember: the mountains will always be there, but your safety comes first. Plan cautiously, tread with care, and let the Himalayas grant you an experience that you will never forget.

FAQs

What are the early signs of altitude sickness?

The earliest to present themselves are headache, weakness, dizziness, loss of appetite, and insomnia. These tend to occur within 12–24 hours following altitude gain.

How do I prevent altitude sickness while trekking in Nepal?

Ascend gradually (300–500m per day above 3,000m), schedule rest/acclimatization days, drink vast quantities of water, avoid alcohol and cigarettes, and adopt a carbohydrate diet. Trekking Planner Nepal coordinates itineraries with acclimatization days to reduce risks.

What can I do if I develop altitude sickness on a trek?

Stop climbing right away. Rest, rehydrate, and observe your symptoms. If they do not get better within 24 hours or if they worsen, descend right away. Let your guide know so they can provide medical assistance or evacuation if necessary.

Is altitude sickness frequent on treks such as Everest Base Camp or Annapurna?

Yes, altitude sickness is widespread on treks like Everest Base Camp (5,364m), Annapurna Circuit (5,416m Thorong La Pass), and Manaslu Circuit (5,160m Larke Pass). Trekkers commonly experience mild symptoms, though acute cases are rare with proper acclimatization.

Can altitude sickness happen even after returning home?

Yes, but rarely. Several symptoms, such as headache, fatigue, or cough, may persist for a few days after descent. For HAPE or HACE under extreme conditions, however, medical consultation is still necessary after returning home.